Strategy Page December 11, 2012

The recent Chinese announcement that it

would begin enforcing new rules, starting January 1st, that will have

Chinese naval patrols escorting, or expelling, foreign ships from most

of the South China Sea has mobilized a lot of resistance. But the

Chinese have been clever about how they will go about this. China is not

planning on having grey painted navy ships do the intercepting and

harassing but white painted coast guard vessels. White paint and

vertical red stripes on the hull is an internationally recognized way to

present coast guard ships. This is much less threatening than warships.

China also calls in civilian vessels (owners of these privately owned

ships understand that refusing to help is not an option) to get in the

way of foreign ships the coast guard wants gone. Thus if foreign

warships open fire to try and scare away these harassing vessels they

become the bad guys.

China has three 1,500 ton coastal patrol ships ("cutters" in American parlance) being built simultaneously, next to each other as part of a 36 ship order. All these are for the China Marine Surveillance (CMS). Seven of the new ships are the size of corvettes (1,500 tons), while the rest are smaller (15 are 1,000 ton ships and 14 are 600 tons). For a long time coastal patrol was carried out by navy cast-offs. But in the last decade the coastal patrol force has been getting more and more new ships (as well as more retired navy small ships). Delivery of all 36 CMS ships is to be completed in the next two years. Meanwhile China is transferring more elderly navy small (corvette type) warships to the various law enforcement agencies responsible for coastal security. As of January 1st China will officially include the coasts of many uninhabited islets, rocks, and reefs in the South China Sea in that jurisdiction. This will make a lot of areas that the rest of the world considers international waters into Chinese coastal waters. China needs a lot more ships to patrol all this.

The CMS service is one of five Chinese organizations responsible for law enforcement along the coast. The others are the Coast Guard, which is a military force of white painted vessels that constantly patrols the coasts. The Maritime Safety Administration handles search and rescue along the coast. The Fisheries Law Enforcement Command polices fishing grounds. The Customs Service polices smuggling. China has multiple coastal patrol organizations because it is the custom in communist dictatorships to have more than one security organization doing the same task, so each outfit can keep an eye on the other.

CMS is the most recent of these agencies, having been established in 1998. It is actually the police force for the Chinese Oceanic Administration, which is responsible for surveying non-territorial waters that China has economic control over (the exclusive economic zones or EEZ) and for enforcing environmental laws in its coastal waters. The new ship building program will expand the CMS strength from 9,000 to 10,000 personnel. CMS already has 300 boats and ten aircraft.

In addition, CMS collects and coordinates data from marine surveillance activities in ten large coastal cities and 170 coastal counties. When there is an armed confrontation over contested islands in the South China Sea it's usually CMS patrol boats that are frequently described as "Chinese warships." The CMS and the four other “coast guard” forces have several hundred large ships (over 1,000 tons, including several that are over 3,000 tons) and thousands of smaller patrol boats. China is building small bases in the disputed islands that can serve as home port for the small patrol boats. It should be noted that many of these patrol vessels are designed to be equipped with heavier weapons (missiles, torpedoes) in wartime.

Thus the current expansion is mostly about the EEZ and patrolling it more frequently and aggressively. International law (the 1994 Law of the Sea treaty) recognizes the waters 22 kilometers from land as under the jurisdiction of the nation controlling the nearest land. That means ships cannot enter these "territorial waters" without permission. However, the waters 360 kilometers from land are considered the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of the nation controlling the nearest land. The EEZ owner can control who fishes there and extracts natural resources (mostly oil and gas) from the ocean floor. But the EEZ owner cannot prohibit free passage or the laying of pipelines and communications cables. China has already claimed that foreign ships have been conducting illegal espionage in their EEZ. But the 1994 treaty says nothing about such matters. China is simply doing what China has been doing for centuries, trying to impose its will on neighbors or anyone venturing into what China considers areas under its control.

For the last two centuries China has been prevented from exercising its "traditional rights" in nearby waters because of the superior power of foreign navies (first the cannon armed European sailing ships, then, in the 19th century, newly built steel warships from Japan). However, since the communists took over China 60 years ago, there have been increasingly violent attempts to reassert Chinese control over areas that have long (for centuries) been considered part of the "Middle Kingdom" (or China, as in the "center of the world").

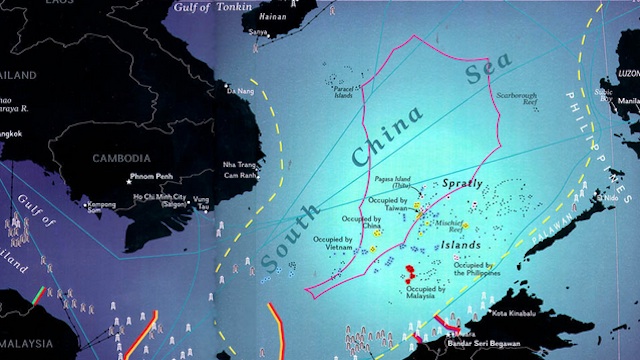

China is particularly concerned about the nearby Spratlys, a group of some 100 islets, atolls, and reefs that total only about 5 square kilometers of land but sprawl across some 410,000 square kilometers of the South China Sea. Set amid some of the world's most productive fishing grounds, the islands are believed to have enormous underwater oil and gas reserves. Several nations have overlapping claims on the group. About 45 of the islands are currently occupied by small numbers of military personnel. China claims them all but occupies only 8, Vietnam has occupied or marked 25, the Philippines 8, Malaysia 6, and Taiwan one.

China prefers to use non-military or paramilitary ships (like those of the CMS) to harass foreign ships it wants out of the EEZ or disputed warfare. This approach is less likely to spark an armed conflict and makes it easier for the Chinese to claim they were the victims. These claims of being a victim come across as a bad joke to China’s neighbors. That’s because the new rules mean offshore areas of the Philippines, Malaysia, Taiwan, Brunei, and Vietnam that international law does not recognize as Chinese are now formally claimed by China. India and the United States have both announced that they will not obey and that Indian and American warships expect to move unmolested through the South China Sea in 2013.

http://www.strategypage.com/htmw/htsurf/articles/20121211.aspx

China has three 1,500 ton coastal patrol ships ("cutters" in American parlance) being built simultaneously, next to each other as part of a 36 ship order. All these are for the China Marine Surveillance (CMS). Seven of the new ships are the size of corvettes (1,500 tons), while the rest are smaller (15 are 1,000 ton ships and 14 are 600 tons). For a long time coastal patrol was carried out by navy cast-offs. But in the last decade the coastal patrol force has been getting more and more new ships (as well as more retired navy small ships). Delivery of all 36 CMS ships is to be completed in the next two years. Meanwhile China is transferring more elderly navy small (corvette type) warships to the various law enforcement agencies responsible for coastal security. As of January 1st China will officially include the coasts of many uninhabited islets, rocks, and reefs in the South China Sea in that jurisdiction. This will make a lot of areas that the rest of the world considers international waters into Chinese coastal waters. China needs a lot more ships to patrol all this.

The CMS service is one of five Chinese organizations responsible for law enforcement along the coast. The others are the Coast Guard, which is a military force of white painted vessels that constantly patrols the coasts. The Maritime Safety Administration handles search and rescue along the coast. The Fisheries Law Enforcement Command polices fishing grounds. The Customs Service polices smuggling. China has multiple coastal patrol organizations because it is the custom in communist dictatorships to have more than one security organization doing the same task, so each outfit can keep an eye on the other.

CMS is the most recent of these agencies, having been established in 1998. It is actually the police force for the Chinese Oceanic Administration, which is responsible for surveying non-territorial waters that China has economic control over (the exclusive economic zones or EEZ) and for enforcing environmental laws in its coastal waters. The new ship building program will expand the CMS strength from 9,000 to 10,000 personnel. CMS already has 300 boats and ten aircraft.

In addition, CMS collects and coordinates data from marine surveillance activities in ten large coastal cities and 170 coastal counties. When there is an armed confrontation over contested islands in the South China Sea it's usually CMS patrol boats that are frequently described as "Chinese warships." The CMS and the four other “coast guard” forces have several hundred large ships (over 1,000 tons, including several that are over 3,000 tons) and thousands of smaller patrol boats. China is building small bases in the disputed islands that can serve as home port for the small patrol boats. It should be noted that many of these patrol vessels are designed to be equipped with heavier weapons (missiles, torpedoes) in wartime.

Thus the current expansion is mostly about the EEZ and patrolling it more frequently and aggressively. International law (the 1994 Law of the Sea treaty) recognizes the waters 22 kilometers from land as under the jurisdiction of the nation controlling the nearest land. That means ships cannot enter these "territorial waters" without permission. However, the waters 360 kilometers from land are considered the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of the nation controlling the nearest land. The EEZ owner can control who fishes there and extracts natural resources (mostly oil and gas) from the ocean floor. But the EEZ owner cannot prohibit free passage or the laying of pipelines and communications cables. China has already claimed that foreign ships have been conducting illegal espionage in their EEZ. But the 1994 treaty says nothing about such matters. China is simply doing what China has been doing for centuries, trying to impose its will on neighbors or anyone venturing into what China considers areas under its control.

For the last two centuries China has been prevented from exercising its "traditional rights" in nearby waters because of the superior power of foreign navies (first the cannon armed European sailing ships, then, in the 19th century, newly built steel warships from Japan). However, since the communists took over China 60 years ago, there have been increasingly violent attempts to reassert Chinese control over areas that have long (for centuries) been considered part of the "Middle Kingdom" (or China, as in the "center of the world").

China is particularly concerned about the nearby Spratlys, a group of some 100 islets, atolls, and reefs that total only about 5 square kilometers of land but sprawl across some 410,000 square kilometers of the South China Sea. Set amid some of the world's most productive fishing grounds, the islands are believed to have enormous underwater oil and gas reserves. Several nations have overlapping claims on the group. About 45 of the islands are currently occupied by small numbers of military personnel. China claims them all but occupies only 8, Vietnam has occupied or marked 25, the Philippines 8, Malaysia 6, and Taiwan one.

China prefers to use non-military or paramilitary ships (like those of the CMS) to harass foreign ships it wants out of the EEZ or disputed warfare. This approach is less likely to spark an armed conflict and makes it easier for the Chinese to claim they were the victims. These claims of being a victim come across as a bad joke to China’s neighbors. That’s because the new rules mean offshore areas of the Philippines, Malaysia, Taiwan, Brunei, and Vietnam that international law does not recognize as Chinese are now formally claimed by China. India and the United States have both announced that they will not obey and that Indian and American warships expect to move unmolested through the South China Sea in 2013.

http://www.strategypage.com/htmw/htsurf/articles/20121211.aspx