Focused on the East Sea Dispute and Solution . Contact via email: trankinhnghi@gmail.com

Monday, November 26, 2012

Friday, November 23, 2012

PH protests new Chinese passport map

by

Carlos Santamaria /The Nation

Posted on 11/22/2012 6:10 PM | Updated 11/23/2012 1:48 AM

Posted on 11/22/2012 6:10 PM | Updated 11/23/2012 1:48 AM

PASSPORT

ROW. The new Chinese e-passport has a map including its 9-Dash line

claim to most of the South China Sea. Image courtesy of www.china.org.cn

PASSPORT

ROW. The new Chinese e-passport has a map including its 9-Dash line

claim to most of the South China Sea. Image courtesy of www.china.org.cn(UPDATED) MANILA, Philippines - The Philippines protested on Thursday, November 22 the decision of China to print on its new e-passport the image of the controversial 9-Dash line showing its claim over virtually the whole South China Sea, contested by the Philippines among other countries.

The Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) sent a verbal note regarding the issue to the Chinese Embassy in Manila read to the media by Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario.

"The Philippines strongly protests the inclusion of the 9 dash line in the e passport as such image covers an area clearly part of the Philippines’ territory and maritime domain," the verbal note said.

In diplomatic language, a verbal note is an unsigned communication considered less formal than a note but stronger than a memorandum.

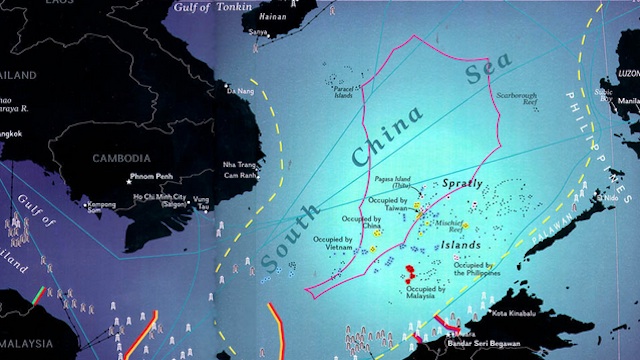

CONTROVERSIAL MAP. Map featuring China's 9-Dash line claim over the South China Sea. Image courtesy of www.southchinasea.org

CONTROVERSIAL MAP. Map featuring China's 9-Dash line claim over the South China Sea. Image courtesy of www.southchinasea.org9-Dash line 'not valid'

The 9-Dash or U-Shaped line is used by China and Taiwan to claim a vast area of the South China Sea (West Philippine Sea) including the Paracel Islands -- occupied by China but claimed by Vietnam -- and the Spratly Islands, also disputed by Brunei, the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam apart from Taiwan.

However, the DFA stressed in the verbal note that "the Philippines does not accept the validity of the 9-Dash line, that amounts to an excessive declaration of maritime space in violation of international law."

"The Philippines demands that China respect the territory and maritime domain of the Philippines. The action of China is contrary to the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea, particularly on the provision calling on parties to refrain from actions that complicate the dispute," the diplomatic communication added.

Finally, the verbal noted reiterated that "the waters, islands, rocks, and other maritime features and continental shelf within the 200 nautical miles from the baselines form an integral part of the territory and maritime jurisdiction" of the West Philippine Sea.

DISPUTED AREA. Google Maps image of the South China Sea

DISPUTED AREA. Google Maps image of the South China SeaReactions in Vietnam, China

Some social media users in China said the maps had delayed them at Vietnamese immigration.

"I got into Vietnam after lots of twists and turns," said one user of China's hugely popular microblogging site Sina Weibo, saying an entry stamp was initially refused "because of the printed map of China's sea boundaries -- which Vietnam does not recognise".

Vietnamese foreign ministry spokesman Luong Thanh Nghi told reporters Thursday that the Chinese documents amounted to a violation of Hanoi's sovereignty and it had protested to the embassy.

Officials handed Chinese representatives "a diplomatic note opposing the move, asking China to abolish the wrongful contents printed in these electronic passports", he said.

Beijing attempted to downplay the diplomatic fallout from the recently introduced passports, with a foreign ministry spokeswoman saying the maps were "not made to target any specific country".

"We hope to maintain active communication with relevant countries and promote the healthy development of people to people exchanges," Hua Chunying added.

WORKING

ON LEGAL CLAIM. China's National Institute for South China Sea Studies

President Dr. Wu Shicun. Image courtesy of www.nanhai.org.cn

WORKING

ON LEGAL CLAIM. China's National Institute for South China Sea Studies

President Dr. Wu Shicun. Image courtesy of www.nanhai.org.cnChina, Taiwan studying legal claim

Chinese and Taiwanese scholars are currently studying borderlines based on the 9-Dash line in order to come up with a definitive legal and historical claim to the region in one year.

The study group, commissioned by China's National Institute for South China Sea Studies, is so far not considering other countries as legitimate claimants.

According to China, the 9-Dash demarcation line first appeared in 1948, before Mao Zedong's Communist Party ousted Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang from power and the People's Republic of China was established.

The borderline is rejected by four members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN): the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia and Vietnam.

The vice foreign ministers of these four countries are set to meet in December in Manila to discuss a multilateral approach to their overlapping claims in the South China Sea.

China - which insists on only bilateral negotiations -- and Taiwan have not been invited. - Rappler.com, with reports from Agence France-Presse

Monday, November 19, 2012

Prospects of Political Reforms in Myanmar

A recent trip I took to Myanmar

(Burma) provided an occasion to reflect on some large and small issues in U.S.

foreign policy, and to think about what works and what doesn’t. My trip came

shortly before it was publicly revealed that President Obama will visit Myanmar

in the second half of November, which will highlight Myanmar’s reform and

opening to the West.

Questions, and tentative answers:

1) Is Myanmar seriously on the path

to reform?

So it would seem. The signs were

abundant on my trip. The senior officials I met spoke convincingly about their

commitment to democratic reform. One Minister positively mentioned democracy

heroine Aung San Suu Kyi’s participation in a recent government-sponsored

workshop. Newspapers published lively debates, virtually free of the

all-pervasive censorship of the last two decades. Pictures of Aung San Suu Kyi

and her father Aung San, the founder of modern Burma, could be seen on the

walls of village restaurants. A large U.S. official human rights delegation

visited in October and met with top Myanmar officials. Ordinary people spoke of

the profound change in atmosphere, and of their willingness to speak out on

matters where there was fear and silence only recently. This change in mood

follows a series of steps disassembling key foundations of the repressive

structure of Myanmar’s military government – release of hundreds of political

prisoners, legalization of the opposition political party National League for

Democracy, legalization of peaceful demonstrations, and revival of talks with

rebellious ethnic groups.

2) What is Aung San Suu Kyi’s role

and what is she doing?

Aung San Suu Kyi remains

unequivocally the most popular political figure in Myanmar. She and her party

decisively won the by-elections in April 2012 after the end of her years of

confinement. There is reason to believe she and her party will win national

elections in 2015 and be in a position to form a government. In preparation,

she is showing a strongly pragmatic streak, reaching out to officials in the

government, bonding with President Thein Sein and speaking positively of them

at her Congressional Gold Medal ceremony. There is grumbling in the overseas

human rights community at her apparent embrace of the compromises of national

politics. She is encountering the inevitable second-guessing that accompanies

the decision to cease to become an icon and to become a political actor, just

as Lech Walesa endured second-guessing when he worked with General Jaruzelski

in Communist Poland in the early 1980’s.

3) Did anyone in the West see this

coming?

Perhaps somewhere someone in the

West foresaw Myanmar’s turn toward reform, but the conventional wisdom

certainly did not. Asia analysts inside and outside the government,

editorialists, and human rights advocates alike all scorned Myanmar’s

installation of a civilian government in April 2011 and its elections last year

as fraudulent, saw little political significance in Aung San Suu Kyi’s release,

and projected a grim political future.

4) How did it happen?

There are many retrospective

theories, none fully satisfactory. One important factor seems to have been a

generalized desire to escape Myanmar’s growing dependence on China by

establishing the basis for renewed relations with the West. Myanmar

historically is a fiercely independent country, having for example quit the

Nonaligned Movement because it felt it was too aligned. Resentment against the

Chinese presence, and its enterprises dominating the extractive industries

while providing little employment for Myanmar nationals, runs deep. Some

Burmese experts, including Thant Myint-U, the grandson of former UN Secretary

General U Thant, presciently wrote of a new mood among the younger Myanmar

officer corps, who have played a central role in spurring reform. Human rights

groups point to the effect of years of sanctions in persuading the leadership

it needed to take a new course. Advocates of engagement credit ASEAN with

helping to knock down the generals’ resistance to the international community.

Within Myanmar, the aging senior generals seem to have confidence they will not

be held accountable for past repressive behavior, and the officer corps

generally is comfortable that its special role in Myanmar politics will be

preserved under a constitution that gives them a privileged and outsized role.

This sense of security among the military old guard may have made them more

willing to accept the current political opening.

5) What was the role of the U.S.

Government?

From 1990 to 2008, successive

administrations, pushed by the Congress, piled sanction upon sanction on

Myanmar – bans on new investment, bans on imports, and designation of people

and companies for financial sanctions. Under George W. Bush, First Lady Laura

Bush played a large role in identifying the regime as a target for further

isolation. In his inauguration speech, President Obama offered to reach out a

hand to adversaries “if (they) are willing to unclench (their) fist. “ That

policy has produced little in the way of positive results around the world,

except in the case of Myanmar. The Administration decided early to open a

channel of diplomatic engagement with the Myanmar leadership, conducted on the

U.S. side by Assistant Secretary of State Kurt Campbell, laying out the agenda

for political reform and nonproliferation by Myanmar that would induce

sanctions relaxation on the U.S. side. The expressed willingness of the U.S.

government on an authoritative level to offer a road map to good relations gave

the Myanmar government an incentive, and confidence, to proceed. The decision

of the Obama administration, in coordination with allies in Europe and

Australia, to significantly ease sanctions earlier this year should provide a

further spur to both desperately needed economic development and political

reform.

6) Are there broader lessons with

regard to sanctions as a tool to change behavior of bad actors?

Sanctions are sometimes the only

effective way for the U.S., and the international community, to signal the

unacceptability of a regime’s behavior. Such was the case for a long time with

Myanmar. So imposition of sanctions was appropriate.

But sanctions, it must be

remembered, are not an end in themselves. As the popular song goes, you’ve got

to know when to hold and when to fold. There is invariably an irresistible

momentum in Washington to continue on the sanctions path whether or not it

gives any indication of leading to positive outcome. Human rights groups

sometimes see sanctions against malefactors as the measure of sound and moral

government policy, and publicize the violations of dictatorial regimes to rally

public support and funding around campaigns that have sanctions as their end

product. The Congress wants to show that it is doing something, whether

effective or not, and sanctioning dictatorial regimes becomes seen as a way to

demonstrate its virtue. This dynamic is evident, for example, in the case of

Cuba. We have now had sanctions in effect for over 50 years toward Cuba, and

their support among American political actors has in no way been weakened by

their manifest strengthening of the Castro brothers’ hold on power. Everyone –

the U.S. political class, the private advocacy groups, the Castros – seems

happy with this state of affairs, with the exception of the Cuban people who

are its victims. Policy toward Myanmar was developing along the Cuban model,

but happily it has now diverged from that path.

7) Is the U.S. Government well

structured to deal with issues like Myanmar?

Since the Carter Presidency, there

has been a growing infrastructure of offices and officials with

responsibilities purely for human rights issues, divorced from broader matters

of foreign policy and national security. These offices have evolved into the

voice of the human rights NGO community within the U.S. government, frequently

serving as a megaphone for the human rights NGOs, seeking their input to State

Department human rights reports, and fighting for the specific measures

proposed by the NGOs. In some ways, this is not radically different from the

way in which other constituencies are represented in the foreign policy

apparatus, e.g. business through the State Department’s Economic and Business

Bureau. But the identification of the human rights offices with their constituency

tends to be more single-minded (note: The current Assistant Secretary for

Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, Michael Posner, in fact has escaped this

straitjacket and acted as a strong advocate for human rights but with a focus

on practical, not symbolic, results and a nuanced awareness of broad foreign

policy objectives).

When I served as Senior Director for

Asian Affairs at the National Security Council during the transition of U.S.

policy toward Myanmar between 2009 to 2011, I chaired a number of interagency

meetings (called Interagency Policy Committees) on Myanmar. Normally, meetings

of this kind are attended by one senior representative of each agency,

accompanied by one more junior person. In the case of Myanmar, no less than

seven offices from the State Department – the East Asia Bureau, the Human

Rights Bureau, the US Mission to the UN, the State Department liaison to the US

Mission to the UN, the US Mission to international organizations in Geneva, the

US Ambassador for War Crimes, and the Refugees Bureau – attended. Agencies at

such meetings are expected to speak with one voice. With seven offices

attending, all seeking to have their voices heard, it was difficult to

impossible for that to happen. Some of them were aggressively seeking creation of

a Commission of Inquiry to look into Myanmar regime war crimes, at precisely

the moment when Aung San Suu Kyi was released from captivity and there were

hints of softening of repression. Only by empowering the Assistant Secretary

for East Asia and the Pacific to speak for the State Department and to conduct

diplomacy without a group from his building looking over his shoulder was the

Administration able to pursue a coherent, and ultimately successful policy.

8) What is the best way to deal with

issues involving bad actors like the Myanmar regime?

The human rights NGOs have an

indispensable role in tracking human rights abuses, highlighting publicly the

offenders and offenses, and mobilizing the international community to censure

them. This is one of the proud features of a democratic society with a

conscience, the activities of these groups of private actors with a strong

commitment to justice even in obscure corners of the globe and their

determination to make victims of injustice heard. Not only should we not ignore

or marginalize such groups; we should celebrate them, and magnify and amplify

their role.

The role of the U.S. government

needs to be different. It should not ghettoize human rights issues. Nor should

it encourage the creation and proliferation of offices that result in the

drawing of lines between officials, all of whom should have as their top

priority our national security and foreign policy success as well as a strong

commitment to human rights. There should not be a small group of people anointed

to express human rights concerns, acting as representatives of the NGO

community, while officials with responsibility for national security and

foreign policy fall into a reflexive response of marginalizing human rights in

response. Our current structure frequently produces formalized battles over

countries that are human rights bad actors. In such cases officials with broad

national security responsibilities tend to roll over human rights when dealing

with countries of major national security concern, like China, Saudi Arabia,

and Pakistan, while deferring to the human rights offices on countries of

lesser foreign policy importance, like Myanmar. This is not a framework built

for success or sound policy development. Our government needs to sensitize our

top national security officials to the need to build human rights issues

more effectively into policy, while reminding the human rights offices that

they too need to have a commitment to broad U.S. national security goals, not

just the advancement of a virtuous NGO agenda.

Thursday, November 15, 2012

A way ahead in the South China Sea

| By David Brown Asia Times Online Nov,8,2012 http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China/NK07Ad02.htmll

A

great deal of unrealistic hope has been invested

in the notion that the Association of Southeast

Asian Nations (ASEAN) will form a bulwark against

China's expansion into Southeast Asian waters. It

has been thought that braced by China's claim of

"indisputable sovereignty" over "relevant waters"

that apparently reach nearly to Singapore, ASEAN

states would articulate a common interest and draw

a line that non-regional powers such as Japan,

Australia, India and in particular the United

States could support.

However, ASEAN operates on the principles of consensus and non-confrontational bargaining, in this instance a fatal flaw. Four of its 10 members - Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos and Thailand - have consistently given priority to preserving cozy bilateral relations

with China over ASEAN

unity. Thus divided, ASEAN's members have jawed

endlessly in search of a framework that will

minimally satisfy Beijing's ambitions.

On this, they have gotten little help from Beijing. China's shirked every ASEAN proposal to set up a conflict-management scheme, including the so-called Code of Conduct in the South China Sea. Beijing won't agree to arbitration of rival claims or even discussions with more than one country at a time. Nor will China even deign to clarify just what it claims in the South China Sea. And so, for two decades, innumerable ASEAN meetings have kicked the can down the road. Four of the 10 ASEAN states are on the frontline of the dispute. Malaysia, Brunei, the Philippines and Vietnam claim sovereignty over all or parts of the Spratly islands, a host of reefs, rocks and islets that sprawl across the southern end of the South China Sea. Control of “land features” in turn generates claims to surrounding sea areas. Vietnam and the Philippines additionally claim islets and reefs farther north nearer to China. For Hanoi, those claims include the Paracel Archipelago, midway between Vietnam's central coast and China's Hainan Island, islets that Beijing wrested from the dying South Vietnamese regime in 1974 and where, early this year, Beijing set up the trappings of a prefecture that supposedly incorporates all of its expansive South China Sea claims. For Manila, the claims cover the Scarborough Shoal, rich fishing grounds only 200 kilometers off the coast of Luzon where in April it came out on the short end of a confrontation with Chinese coast guard cutters. Not surprisingly, it is the Philippines and Vietnam that have campaigned most vigorously for a robust answer to Chinese pretensions to domination of the seas stretching nearly 2,000 kilometers south from Hainan Island. Manila’s and Hanoi's eagerness to engage US naval might as a factor in the dispute has prompted tut-tutting among some of their ASEAN brethren. By contrast, Malaysia and Brunei have maintained a decidedly low profile. They have sorted out their claims between themselves and with Vietnam, relying on concepts codified in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and customary international law. Both have stood aloof from Vietnamese and Philippine efforts to defend their claims in the seas to the north. Uncharitable though the thought may be, both Kuala Lumpur and Bandar Seri Begawan seem to have hoped against mounting evidence that China's appetite could be satiated short of the waters they claim. Indonesia and Singapore also share an interest in discouraging China from pursuing its expansive claim. The seas within China's infamous nine-dash line overlap Indonesia's exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the vicinity of the Natuna Islands. Jakarta and Singapore have until now distinguished themselves as the prime backers of an "ASEAN solution", with Singapore as usual deferring publicly to Indonesia's leadership. While professing to be ready to work things out bilaterally, China hasn't budged from its claim of historic rights in all of the waters within the nine-dash line. Beijing is thus asserting ownership of maritime resources in upwards of 85% of the South China Sea, notwithstanding the UNCLOS rule that all nations have exclusive sovereign rights to exploit adjacent seas out to 200 nautical miles from their coast, or beyond if their continental shelf is wider, unless they abut on another nation's EEZ. China has consistently refuted UNCLOS rules, claiming Its sailors and fishermen have plied these seas since time immemorial. All of the claimants can invoke historical precedent to justify their claims. For millennia, the South China Sea has been a global commons. Vietnam can produce stacks of 18th century maps and decrees that demonstrate a considerably more consistent interest than China in exercising sovereignty over various South China Sea atolls. As in China, these yellowing documents stoke nationalist passions. Historical argument, however, does not offer a way out of the tangle of claims unless, as at least some players on the Chinese side believe, it is backed up by irrefutable force. Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi famously declared at an ASEAN-hosted meeting in August 2010 that "China's a big country and other countries are small countries and that is just a fact." Roiled waters For several years now, hopes of a diplomatic breakthrough have risen in the autumn months, while the South China Sea is roiled by monsoons. Come calmer weather, Beijing's provocations multiply, directed in particular at harassment of Vietnamese and Filipino fishermen and at scaring off energy companies that presume to prospect for seabed oil and gas under licenses granted by Hanoi or Manila. Beijing has relied on hundreds of armed "maritime safety" and "fisheries protection" vessels to extend its control, while over the horizon is the increasingly potent People's Liberation Army Navy. Not surprisingly, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore have redoubled efforts to build up their own air and naval strength. The Philippines is a latecomer to the South China Sea arms build-up. Though Manila has been energized by recent clashes with China, its forces are particularly outgunned. It is the expected bonanza of seabed oil and gas, encapsulated within long-frustrated resentment of foreign affronts, that is driving China's attempt to bring the South China Sea under its sway. The failure of ASEAN confabulations to find a way out of the growing crisis, China's relentless application of a "talk and take" strategy, and the consequent engagement of the US in these quarrels has driven experts to despair. It is apprehension of how a revanchist China might dispose itself should it prevail in the current contest that has roused the US. Washington is not itching to fight and it is still unclear how the US might respond if Vietnam or the Philippines or even Singapore were obviously slipping into a Chinese sphere of influence. There seems little doubt, however, that Washington is determined to prevent Beijing from controlling navigation through the South China Sea. If ASEAN won't fill the breach, who will? The US and the rest of the world require a solid argument to justify sustained and effective engagement. Recently burned by the weapons of mass destruction chimera in Iraq, the American public is wary of another foreign military adventure. Japan is congenitally wary of an assertive posture. If they want more from the US and its allies than expressions of determination to uphold freedom of navigation through the South China Sea, the Southeast Asian nations on the sea’s littoral must make a compelling case that they need and merit assistance. Many in the Western foreign policy establishment believe that the US ought to make a partner of “rising China.” Rising tensions in the South China Sea are a threat to their vision of a peaceful and prosperous Pacific community. Ready to concede a sphere of influence to China, they say - like ASEAN - that they won't take sides in the dispute. Many Western "strategic thinkers" still discuss the confrontations as though all parties are equally culpable. This perception, however, can be changed. All that is needed is for Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam to negotiate a common position - which they can do by sorting out, if not settling, their claims amongst themselves by applying the precepts of the UNCLOS and general international law. They could also commit to arbitration of remaining disputes. Non-claimants Indonesia and Singapore could support such an ASEAN state process. The immediate outcome should be clarification of these four nations' currently overlapping claims to the Spratly Group's islands, reefs and rocks. They could aim to agree on the "maritime space" these land features generate, and thus establish the geographical limits of the disputed areas. That would in turn clarify the implications of these claims for control of surrounding seas. Regarding claims outside of the Spratly area, a poor bargain is arguably better than none at all. China has controlled the Paracels for nearly four decades and now seems determined to hold the Scarborough Shoal as well. At this point, successful assertion of historic rights by Vietnam and the Philippines over these contested territories seems a forlorn hope. A pragmatic course would be to insist on Beijing's recognition of EEZ's generated according to UNCLOS rules, a course which if upheld may return a western slice of the Paracels to Vietnam as well as the Scarborough Shoal to the Philippines. This much Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia and Singapore ought to support, though they have shied at endorsing claims of historic right. These steps, perhaps arrived at after a few months of intense and secret negotiation, would establish a foundation for peaceful resolution of what is now undeniably a crisis. It would also give the US and its friends a sound basis for robust support, and even - should it come to that - military intervention. Historical baggage China, with its leadership renewed and set for the next several years, may by then be looking for a way back from confrontation. Chinese spokesmen have said on occasion that claims should be settled according to international law, and that pending such resolution agreements on the joint exploitation of South China Sea resources can serve to reduce tensions. It will not be easy, however, for China to back away from its historical claims. Such a retreat is inconceivable unless Vietnam does the same - that is, unless Hanoi also agrees to establish maritime boundaries based solely on UNCLOS and related principles of international law. Like China, Vietnam is heavily invested in historical arguments. Indeed, some independent scholars say that based on the historical evidence Hanoi's claim to the contested islets is superior. It will be no easier for Vietnam to put history on the shelf; it is, after all, a nation that has forged its identity beating off Chinese invasions every few hundred years since 938 AD And yet, unless these ancient and asymmetrical rivals can rise above this bitter history, there is scant chance of a happy ending to the current South China Sea crisis. Some will argue that dismissing China's historical claims and putting forth a jointly established negotiating position based on sound legal principles will simply infuriate Asia's rising superpower. However, it is hard to imagine that failure to resist Chinese pretensions can lead to a better result. There is still a potentially hopeful scenario. Motivated by a realization that time has run out, the four ASEAN claimants work out sea boundaries amongst themselves by applying relevant legal principles. Supported in concept by Indonesia and Singapore, if not ASEAN collectively, they announce their readiness to enter negotiations with China on the same basis. Instead of denouncing what's been accomplished thus far or insisting that it will only negotiate bilaterally, China agrees to the process. Before long a deal is hashed out that acknowledges China's mastery of most of the Paracels and toeholds in the Spratlys. These parties then turn to discussion of related matters, for example a Code of Conduct. This would not be the same watered-down document that ASEAN has discussed but a robust document that supports the territorial accommodations discussed above. Joint exploitation of energy resources could bind together the various elements of a constructive future in the South China Sea. The parties could then agree to an 'open door' for entities from all the littoral nations subject to responsible behavior. Put another way, any regime for governing the South China Sea cannot endure unless it assures fair access for Chinese entities to the region's maritime resources. The other littoral states must welcome and facilitate Chinese investment and joint ventures, including Chinese participants to exploit seabed hydrocarbons. Fisheries could be managed jointly and sustainably and joint patrols could enforce the agreed rules. Finally, the littoral states and the principal maritime nations could negotiate rules governing shipping channels, notifications and rights of navigation within the South China Sea. Some may protest that this happy scenario would be fatal to the organizational principles and leadership practices that embody the so-called "ASEAN Way." But acknowledging that in this instance ASEAN has failed to make the consensus model work is likely to be less corrosive of the organization's overall effectiveness than continuing an ineffectual effort to assert ASEAN's centrality in the intensifying disputes. David Brown is a retired American diplomat who writes on contemporary Vietnam. He may be reached at nworbd@gmail.com. (Copyright 2012 Asia Times Online (Holdings) Ltd. All rights reserved. Please contact us about sales, syndication and republishing.) |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)